Despite cloud and file servers on the corporate network, users still store important files on the local hard drives of their workstations or laptops. Modern solid-state drives (SSDs) lull users into a deceptive sense of security: Thanks to technologies such as self-monitoring analysis and reporting technology (S.M.A.R.T.) and wear leveling, these data storage devices can predict their demise and usually warn the user in time before a disk failure. However, valuable data is rarely lost by spontaneous disk failure. More often, the cause of data loss is the users themselves accidentally deleting or overwriting files. If you travel with your laptop, you also have to worry about losing the device or damaging it irreparably.

A device and its operating system and applications can be replaced quickly, but it’s a different story for user files. Therefore, every user with important files on their local computer needs a viable backup and restore strategy that covers the following functions:

- Multilevel file versioning

- Local backup

- Remote backup over local area network (LAN)

- Optional remote backup over wide area network (WAN)

- Backup and recovery independent of the operating system

On the free market, all common operating systems have tons of backup programs – many with inexplicably confusing user interfaces. For most users, the backup chain ends at the USB drive, but if you want to back up your data, it is better to use a network share. Common cloud backup tools, on the other hand, back up directly to the connected cloud and therefore only work if you are online.

Backup with Git

The Git tool supports code versioning, shows the details of the differences between saved versions, and allows multiple developers to work together on a project. Because it works online and offline, this popular open source application is more or less a perfect backup program; moreover, it is available for all common operating systems. The backup format is openly documented – independent of the operating system and filesystem – and not a proprietary file format.

Anyone who creates a Git repository first creates an object store with copies of the selected data. This object store keeps track of the changes in the files saved in it. As soon as the user makes a “commit” (i.e., a snapshot of the files), Git remembers the changes to the previous version. Users can roll back the entire repository or individual files to previous versions if they want and recover accidentally deleted information from a previous snapshot.

However, Git does not just back up its repository on the local system. Users can create one or more remote copies of the repository and upload the versions there. Luckily, remote repositories do not need to receive every single commit immediately. A user can write many consecutive commits to the local repository and then send an update to the remote repository. Git’s delta mechanism will submit all missed commits from the local repository so that the remote repository ends up containing all intermediate steps.

Git is also very flexible when it comes to restoring. You can conveniently access previous versions of individual files or entire directories at the command line or in one of the many available Git user interfaces (UIs). When doing so, you do not need to overwrite the existing version but can save an earlier version under a different name. You also have a wide choice of Git servers and, here too, you can view, modify, or download individual files on the web UI, if required.

Git on Windows

The Git homepage offers a setup for Git on Windows. In addition to the plain vanilla command-line (CLI) tool for the Windows prompt and PowerShell, Git also provides the necessary OpenSSL libraries and tools and a MinGW environment, the native Windows port of the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC), that lets Windows administrators run Git from the command line or in PowerShell, as well as in Git Bash.

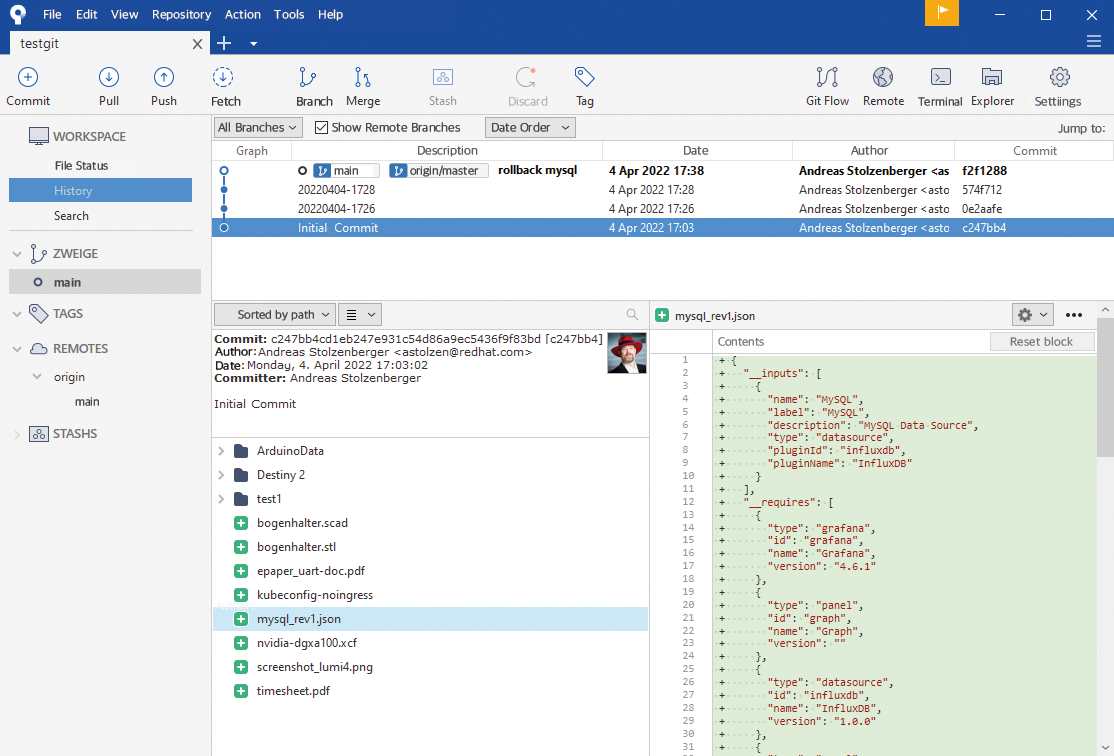

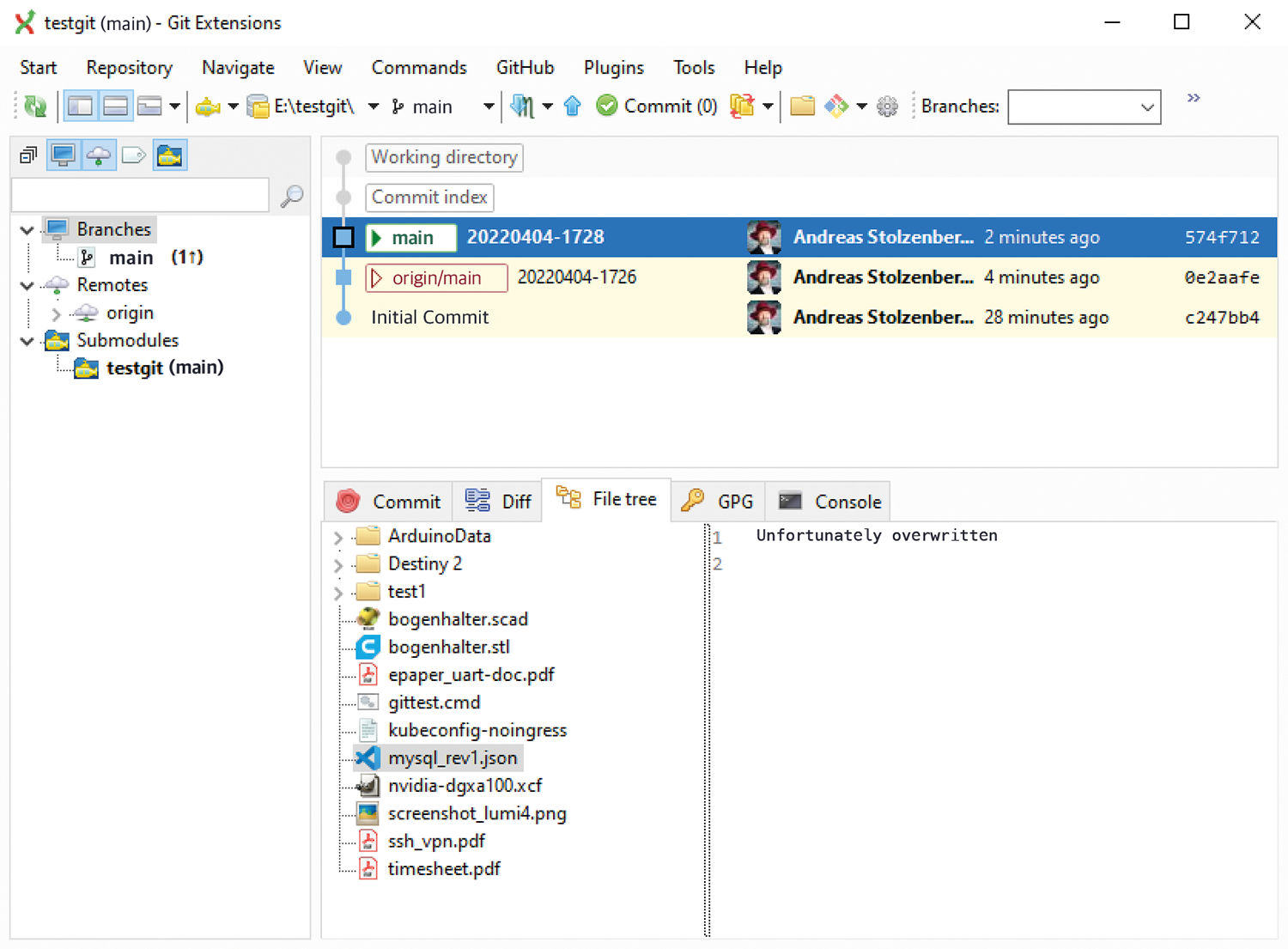

Windows also has a number of graphical UI (GUI) tools for Git. The popular GitHub Desktop is primarily aimed at application developers; however, this tool does not give you a very good overview, especially for large repositories. Although it is not open source, Atlassian provides its Git client Sourcetree free of charge (Figure 1). The client can be used for both development and backup repositories. Git Extensions offers a somewhat older, technically overloaded look and feel (Figure 2). In return, this free client is extremely fast and includes many features.

If you use the Eclipse development environment, the JGit tool, written in Java, is included. Unlike the conventional Git client, JGit also handles the Amazon Simple Storage Service (S3) protocol. If you want to store your repository somewhere instead of, or in addition to, the regular Git server, you can use JGit to move directly into an S3-compatible object store.

Distributing Local Git

For version control, Git creates the versioned repository in the .git subdirectory within the folder to be backed up. However, this does not work for the backup scenario here. The key to success is the ‑‑separate‑git‑dir parameter when creating the repository, which tells Git not to create the object store for versioning in the directory, but on a different path. In this case, .git is not the directory with the files, but a text file with the link to the external directory (i.e., it acts independently from the operating system and filesystem).

In this example, you will be creating a Git repository inside the regular user directory for documents and using a USB drive with driver letter H: for the object store:

mkdirh:\git_backup cd %HOMEPATH%\Documents git init ‑‑separate‑git‑dir=h:\git_backup git add ‑A

If you have not used Git on the system before, the tool will ask you for global variables such as your username and email address; then, it creates the object directory on the USB drive. Depending on the volume of data in the document directory, this step can take some time. In this setup, Git writes its data at a rate of about 1.2GB per minute. The speed also depends on whether Git needs to write small or large files. During the write process you will see a number of warnings, such as:

warning: LF will be replaced by CRLF in <filename>

This message refers to the old dilemma that *nix systems define the end of line (LF, line feed) in a text file differently from Windows (CRLF, carriage return-line feed). Because Git works independent of the operating system, it always saves text files within the object memory in *nix format but leaves the original file unchanged. This automatic conversion should not bother you unless you are restoring a text file stored in Git without the Git tool. For example, if you download a text file from your repository over HTTP from a Git server with a web UI, no CRLF reconversion takes place.

Now that Git has copied all the data to the local repository, you can create a snapshot of the current state with a commit:

git commit ‑m "Repository created"

Now, if you make changes to files, Git tracks them and saves them for the next commit. Each commit is given a unique ID and, for clarity, a name that you pass in with the ‑m parameter – in this case Repository created. Later, you can see in the Git history exactly which files changed in which commit, but if you add new files to the directory, Git does not automatically include them in the repository. You need to run a git add ‑A again before committing. To automate the process, create a suitable batch file:

set commitname=U %date:~‑4%U %date:~‑7,2%U %date:~‑10,2%‑U %time:~‑11,2%U %time:~‑8,2% set gitdir=%HOMEPATH%\Documents cd %gitdir% git add ‑A git commit ‑m "%commitname%"

Now you can create a shortcut on the desktop and trigger the backup at the push of a button. Alternatively, create an automatic task that performs the backup regularly (e.g., every hour), but keep in mind that Git, like any other program, cannot include open files in the snapshot. Of course, the script can be prettified – for example, to check first whether the USB target disk is connected to the system before triggering the backup and initiating an upload to the server once a day.

Now, to restore a single file to a previous state after an accidental change, use git restore as in Listing 1.

Listing 1: git restore

type mysql_rev1.json

Unfortunately overwritten

git log mysql_rev1.json

commit 780...

Author: Andreas ....

2200404-1300

...

git restore --source 780... mysql_rev1.json

type mysql_rev1.json

{

"__inputs": [

{

"name": "MySQL",

"label": "MySQL",

"description": "MySQL Data Source",

...

Git Server Selection

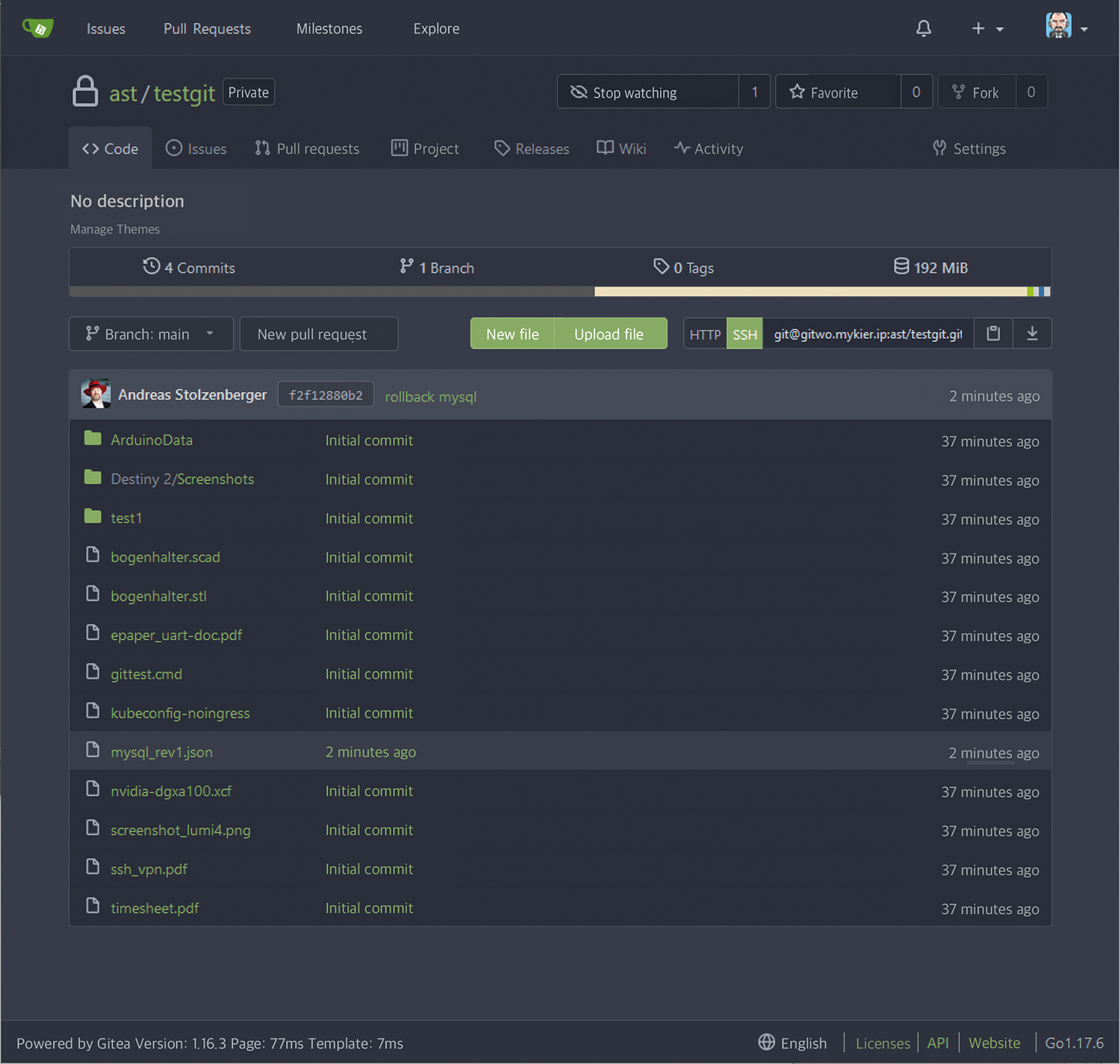

One of the most popular self-hosted Git servers is GitLab, which of course also runs on the service at gitlab.com. However, the massive GitLab, written in Ruby, requires quite a bit of performance on the part of the server hardware. In return, GitLab delivers a wide range of functions, such as a wiki, a bug tracker, and an integrated container image repository. If you only use a Git server as a backup target, you don’t need all of these features and are better off with a simple, but agile, Git server like Gitea, which handles many databases and runs in containers with low resource requirements (Figure 3). For administrators with a predominantly Windows background, the free Bonobo Git Server in .NET integrates directly with Internet Information Services (IIS).

To create a second, remote backup of a local repository, you need a Git server. Here, too, you have a whole range of open source offerings. Gitea is the simplest solution for newcomers. Written in Go, it derives from Google’s in-house Git server Gogs but is maintained by a somewhat more liberal developer community than the Google original. Like Git itself, Gitea is available for all major platforms, so the server service also runs smoothly on Windows. All you need is an existing Git installation and a database. Gitea supports MySQL and PostgreSQL as well as Microsoft SQL Server (MSSQL) or, for simple test setups, SQLite. Of course, Gitea can also be run in a Podman or Docker container.

Once started, Gitea listens on ports 3000 (HTTP) and 22 (SSH) by default. In the simple and clear-cut web UI, you first need to create the user accounts. To avoid the need to log in with a username and password, you will want to use SSH keys to authenticate. The key pairs usually are generated with a centralized key management system and then assigned to the users. In smaller environments, however, users on the client PCs can create key pairs themselves with ssh‑keygen. Remember always to keep a copy of the SSH keys outside the client PC.

With the remote server running, you first log in to the Gitea UI with your user account, where you store the public SSH key, if this has not already been done elsewhere. In your account, you then create an empty repository for the backup data and mark it as a Private repository. Gitea returns the appropriate SSH URL. Now you can add the remote storage path origin to the existing local repository,

git remote add origin U git@<Server>:<User/Repository>.git

and copy the local repository, including all previous commits, to the remote server:

git push ‑u origin main

The ‑u lets you define the remote server origin as the default upstream server for the repository. Future changes can then be sent to the origin server with the git push command, without any additional parameters. Git lets you specify multiple remote repositories and use

git push <name>

to send the updates to different servers.

The Git server can run on the company LAN as well as on a cloud system or in the demilitarized zone (DMZ) with an Internet connection. Because communication between the client and server relies on SSH encryption anyway, the cloud backup to the in-house Git server is secure even without a virtual private network (VPN). Either the web interface of the Gitea server on port 3000 should be protected by a reverse proxy/load balancer with HTTPS termination, or the service itself should run on HTTPS with a suitable certificate. To do this, modify the configuration of Gitea in ./gitea/conf/app.ini and expand the following section:

[server] PROTOCOL = https ROOT_URL = https://<URL>:<Port> HTTP_PORT = <Port> CERT_FILE = cert.pem KEY_FILE = key.pem

Hosted Git services such as GitHub or GitLab are obviously out of the question as backup targets because they limit the size of the repositories.

Git in Git

Once you have familiarized yourself with the Git tool, you can optimize its use. For example, if you are just working on a project for a certain period of time, you can back up all related data to a separate directory and therefore to a separate Git. If the folder is inside an existing repository, Git notices and excludes the project directory as its own repository from the underlying Git.

The user then backs up two repositories: The document directory itself and the project. Thanks to Git’s group features, project data can be shared between workgroups and checked out to multiple clients. When the project is completed, the clients can delete the local project directory, and the Git server keeps all the data as an archive that is available to users at any time.

Conclusions

Backup and version control are closely related topics, so Git is a very good choice as a backup tool for user data. Of course, Git does not back up the operating system or the installed applications or their configuration in the registry.

This article originally appeared in ADMIN magazine and is republished here with permission.

Want to read more? Check out the latest edition of ADMIN Network & Security.

Looking for a job?

Sign up for job alerts and check out the latest listings at Open Source JobHub.

Comments