Most users familiar with Linux have probably used cron or at to schedule the running of commands. Both can be useful in their place: cron for repeated scheduling of events and at for scheduling an event once. However, what both lack is the ability to gather system information and respond to it unless you write a specific script. Usually, it is much easier to use watch and fswatch to do both these things. While watch and fswatch can be used simply to gather information or to check for possible security incursions, both can be tweaked to act like a scheduler with little effort and minimal script-writing ability.

watch

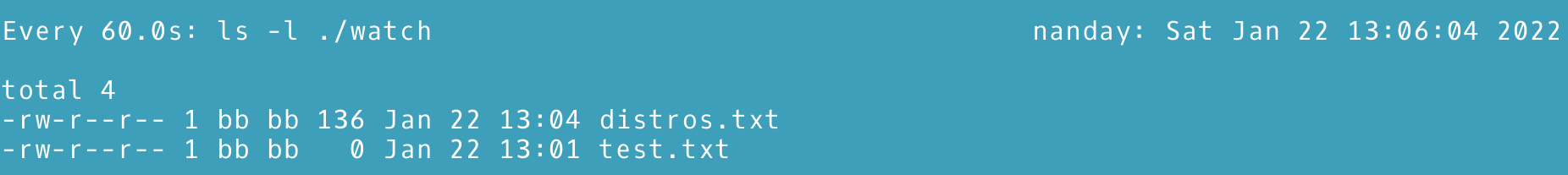

The purpose of watch is to follow how a command’s output changes over time (Figure 1). This information can be used for troubleshooting, as well as for keeping a root or regular user informed about system changes as new packages are installed or updated. In limited circumstances, it could also be used as a simpler replacement for at or cron. Several other common uses are shown in Table 1. By default, watch runs every two seconds until closed or interrupted. The basic command structure is:

watch OPTIONS COMMAND

watch ‑n 5 date |

Display the date every five seconds |

watch ‑n 60 from |

Watch for mail every 60 seconds |

watch ‑d ls ‑l |

Watch changes in a directory |

watch ‑d 'ls ‑l | fgrep joe' |

Watch files owned by the joe account |

watch uname ‑r |

Watch for installation of a new kernel |

watch ‑d free ‑m |

Watch changes in disk spaces |

Depending on the command’s contents, watch may need to be inside quotation marks. For example, a command would need quotes if it uses a pipe in order to run less or grep. Alternatively, instead of quotes, you could run ‑‑exec (‑x), so that a new process is not needed when the command contains multiple commands.

Two options set the nature of watch’s behavior. The most important is ‑‑interval SECONDS (‑n SECONDS). The ‑‑interval option overrides the default ‑2 seconds between each time the command is run – an interval obviously chosen for immediate troubleshooting. However, on a computer that is always running, setting the interval to 86,400 would make watch run once per day, and setting the interval to 604,800 would make it run weekly, making watch serve the same function as at or cron. Either a comma or a period can be used to write large intervals; the minimal interval is .1 second. The only difference between watch and other schedulers is that you would need to remember to restart watch if the computer was ever shut down, which is a problem that at or cron do not have. For reasons that are not clear, the interval can be supplemented with ‑‑precise (‑p) to make sure that the interval is precise – perhaps some testing might require that precision.

watch also supports options to customize output and exit behavior. With ‑‑color (‑c), output is color-coded. With ‑‑no‑linewrap (‑w), long lines are truncated, while ‑‑differences (‑d) highlights the latest output that differs from previous output. You can also remove the header showing the interval, command, current date, and time with ‑‑no‑title (‑t). Exit options are equally varied. With ‑‑chgexit (‑g), watch exits when the output changes, which can be an obvious and handy indicator. Possibly, too, you may want ‑‑beep (‑b) for a noise to indicate that watch has just exited with an error or

‑‑errexit (‑e), which stops output after an error occurs but waits to exit until any key is pressed.

fswatch

fswatch monitors changes to directories or files. Ubuntu users can install it via the fswatch package. The simplest way to use it is to run fswatch in one terminal and edit files in another. As you start to use fswatch, you need to know something about how the command is structured and operates. fswatch is capable of using several different utilities. On macOS, it reports on information gathered by FSEvents. On BSD, it relies on the kqueue monitor. On Linux, it uses inotify, a Linux kernel subsystem, by default with the option of the poll monitor, which saves the time at which files were modified. All these monitors give similar information, although fswatch’s man and info pages warn that each has its own strengths and weaknesses, as well as its own bugs, all of which are described in detail in the help pages. You can use the ‑‑list‑monitor (‑M) option to see a list of available monitors and select which one to use with ‑‑monitor NAME (‑m NAME). However, the output, which displays in the terminal in which the command is running, generally differs little with the monitor.

Without any options, fswatch only records the files that have changed, but other options can add additional information, such as the event detected, and, optionally, the time the event was detected. Event types are self-explanatory. One action may have more than one event type. fswatch event types include:

CreatedUpdatedRemovedRenamedOwnerModifiedAttributeModifiedMovedFromMovedToIsFileIsSymLinkLink

To help organize the output, you can use ‑‑batch‑marker CHARACTER to separate out each loop of the command. In addition, ‑‑print0 (‑0) can be used to ensure that lines are separated for easier reading.

The basic command structure is

fswatch OPTIONS PATHS

As well as specific paths, you can use select paths with regular expressions using ‑‑include REGEX (‑i REGEX) or ‑‑exclude REGEX (‑e REGEX). Searches can be made case insensitive with ‑‑insensitive (‑I) and include subdirectories with ‑‑recursive (‑r). If the watched files include symbolic links, fswatch will follow them if the ‑‑follow‑links (‑L) option is added. You can also use ‑‑timestamp (‑t) to add the local time to the output or ‑‑utf‑time (‑u) to add the time in UTC format. With either time option, you can structure the date using ‑‑format‑time FORMAT (‑f FORMAT), using the strftime codes. Other useful options are ‑‑one‑event (‑1), which exits fswatch after one set of events, and ‑‑latency SECONDS (‑l SECONDS), which must be at least .1 seconds. Unlike watch, fswatch does not give any output, except for briefly outlining the tab of another terminal whose present working directory is open.

Often, the basic information generated by fswatch is useful by itself. However, like watch, fswatch can be used to issue commands. It does so by piping it through xargs, whose purpose is to issue other commands. Table 2 shows four common examples cribbed from fswatch’s online help.

|

Action |

Command |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Run a Bash command |

|

Usually for creating, updating, or deleting files |

|

Watch one or more files and/or directories |

|

– |

|

Print the absolute paths of the changed files |

|

– |

|

Filter by event type |

|

Usually for creating, updating, or deleting directories |

Two More For the Toolbox

If you prefer to work from a desktop environment, Gnome offers command‑runner‑applet with approximately the same functionality as watch and fswatch. But command‑runner‑applet is not a single command; according to its GitHub page, it takes over the desktop while running, although mouse and keyboard actions will run after it completes.

Both watch and fswatch, on the other hand, offer a wider range of functionality within a single command, and fswatch in particular offers in-depth reporting options. The main difference, of course, is that watch provides a unified way to monitor with commands, while fswatch is concerned mainly with the management of directories and files. Each, though, is yet another example of how the command line can offer more than the desktop. Although relatively unknown, each is a useful addition to the administrative toolbox.

This article originally appeared in Cool Linux Hacks and is reprinted here with permission.

Want to read more? Check out the latest edition of Cool Linux Hacks.

Comments