In legacy IT, dynamic scaling usually meant that you had to start new virtual machines manually. Then, you had to integrate the application into an existing cluster and possibly reconfigure the load balancers. Kubernetes takes all of this work off your plate. The

kubectl scale deployment/webserver --replicas=5

command tells Kubernetes to launch five instances of the web server container and makes sure they are running and reachable. Houston, we have load balancing.

The downside is that this only works as long as enough resources are left in the cluster. If the resources are exhausted, you need to add new nodes. Although this might be easy to set up, it means purchasing new hardware and facing a wait, during which the service is not available at the desired performance level. Moreover, if you use autoscaling, Kubernetes can reach its hardware limits without anyone noticing.

One way to bridge the resource gap is to migrate to a public cloud. In the simplest case, you just lease the required resources in the form of virtual machines (VMs) and link them to your cluster. To do this, the existing cluster and the nodes in the cloud need to be able to reach each other directly, either by public addresses or over a VPN connection. Another option is to federate Kubernetes clusters, which gives you the option of docking resources from a second, standalone cluster onto your own and running your applications on both. The software for this is available from the Kubernetes Cluster Federation project (KubeFed).

Installation

In the following example, I assume you already operate a Kubernetes (K8s) cluster. The example uses a managed K8s cluster in the AWS cloud as the extension, but apart from the details of accessing it, the installation described here will work with any other Kubernetes cluster.

The KubeFed documentation describes how to install with the use of the Helm Charts packaging format. In the first step, add the KubeFed repository to the locally installed Helm Charts and check the results:

# helm repo add kubefed-charts https://raw.githubusercontent.com/kubernetes-sigs/kubefed/master/charts # helm repo list kubefed-charts https://raw.githubusercontent.com/kubernetes-sigs/kubefed/master/charts

If everything worked, Helm now has multiple versions of the chart. The command

# helm search repo kubefed

delivered version 0.9.0 in our lab, which is used as a parameter when importing the chart:

# helm --namespace kube-federation-system upgrade -i kubefed kubefed-charts/kubefed --version=0.9.0 --create-namespace

The next step is to add the first cluster to the federation. To manage the federation, download the kubefedctl tool and copy it to /usr/local/bin/ for ease of use.

kubeconfig Files

The Kubernetes site states that "... a kubeconfig file ... is a generic way of referring to configuration files. It does not mean that there is a file named kubeconfig." Access to the Kubernetes cluster(s) is controlled by the default kubeconfig file, ~/.kube/config. This YAML file contains quite a bit of information for each managed cluster, including the cluster itself with a certificate authority (CA) certificate, a name, and an endpoint for access (the cluster entry). Additionally, the user data includes either a certificate and private key, a token for a service account, a script, or a username and password (the user entry).

Last but not least, a context binds one user entry and one cluster entry together. The file also contains the current-context entry, which describes which of the contexts is the default if you do not specify one when calling kubectl. You can easily edit the file with a text editor or use kubectl to do so. The names used in the file are for mutual reference only.

A command like

# kubefedctl join earth --host-cluster-context=earth

adds an initial cluster to the federation. In this example, earth is the name of a cluster context from the ~/.kube/config file. Next, check the status of the cluster:

# kubectl -n kube-federation-system get kubefedclusters NAME AGE READY earth 41h True

While researching this article, I encountered a minor problem in the lab environment. Because the user was named kubeadm and the cluster kubernetes, the cluster context was named kubeadm@kubernetes. However, the at sign interfered with kubefedctl, and the join did not work until I changed the name manually.

Second Cluster

With the major public cloud providers such as Amazon Web Service (AWS) or Google Compute Engine (GCE), you usually have two options for running Kubernetes. Either normal virtual machines are used, on which you install K8s yourself, or the provider has ready-made K8s clusters available as part of a platform-as-a-service offering. Virtual machines also launch in the background, but you see the cluster as the transfer point.

An AWS-managed offering named Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS) was used for this example. Although creating this cluster basically means pressing a button, you do need to set up some environment parameters beforehand, including:

- the subnets in the availability zones where the cluster's working nodes will run (at least two nets in two zones),

- an authorization role for the nodes in AWS – within the AWS infrastructure, this role defines the other resources the Kubernetes nodes can use and how they can use them, and

- a security group with firewall rules that control the traffic coming into the Kubernetes cluster.

The Kubernetes cluster comprises two components: the control plane (i.e., the cluster) and the node group, to which the containers running in Kubernetes are distributed. An additional link runs between the local data center and the AWS cloud. In principle, the entire cluster could be addressed directly over the Internet, but this option would just add attack vectors.

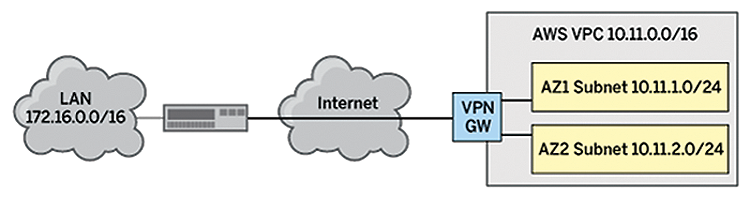

In a business setting, you would set up a site-to-site VPN connection between your data center and the AWS environment. Accordingly, the Kubernetes cluster and all applications running in it only have private IP addresses and can only be reached within the AWS environment or over the VPN. The security groups for network access also only contain the private IP addresses of the AWS environment and the local data center as sources.

I do not run the Kubernetes cluster permanently in AWS but only enable it when needed. The AWS orchestration tool CloudFormation and Ansible help you create all the components as a stack in AWS, providing the local firewall with a VPN tunnel to the environment and adjusting the routing on the local Kubernetes node so that users can reach the cluster in AWS. Figure 1 shows the infrastructure with this setup. On the AWS side, IP addresses are assigned from the 10.11.0.0/16 subnet. The Kubernetes cluster itself needs service addresses from a non-local network – in this specific case, 10.5.0.0/24. The thick black line in the figure represents the VPN tunnel over the Internet.

To be able to access the cluster in AWS in a configuration with kubectl, or with the API, you need to add matching entries to the .kube/config file. The AWS command-line interface (CLI) gives you a separate command for this,

aws eks update-kubeconfig <cluster-name>

which adds the required entries. On the management machine, besides the Kubernetes tools, the AWS CLI also needs to be installed and configured to have access to the AWS account.

The entries in the .kube/config file for the EKS cluster look similar. However, instead of logging in with a token, you log in with the output of a command. In the background, kubectl runs the

aws eks get-token --cluster-name vulkan

command, where vulkan is the name of the Kubernetes cluster in AWS in this example. In the Kubernetes config file syntax, the whole user entry then looks like Listing 1.

Listing 1: User Entry

- name: kubernetes-eks-user

user:

exec:

apiVersion: client.authentication.k8s.io/v1alpha1

command: aws

args:

- eks

- get-token

- --cluster-name

- vulcan

Because the arguments of the command form a field, you write them as a YAML list one below the other. The cluster context is also named vulcan. If something goes wrong, it is best to scroll to the beginning of the command output, which usually has the most relevant part of the information. The remainder is a stack trace, some of which can be very long-winded. If everything works, a call to kubectl,

# kubectl -n kube-federation-system get kubefedclusters NAME AGE READY earth 2h True vulcan 5m True

confirms that the federation now comprises two clusters.

Deployment

Before deployment can start, you need to federate the resource types you want to deploy. These can be pods, services, namespaces, and so on. Again, the kubefedctl tool is used for this step. For example,

kubecfedctl enable pods

lets you distribute resources of the Pod type. If a Kubernetes namespace exists that you want to federate as a whole, you can do so with the command:

# kubefedctl federate namespace demo --contents --enable-type

The --enable-type option ensures that the missing types are also federated immediately. On top of this, you can create a FederatedNamespace type resource that lets you control at namespace level the clusters on which K8s creates resources. This even works at the single deployment level, but it does cause more administrative overhead. However, if you rely on cloud providers where privacy concerns exist, this method gives you clear control over where containers are running.

Setting up a namespace the right way for use in a federation also means having a YAML file like the one in Listing 2. The fedtestns namespace has to exist before the create step. The placement parameter lets you manage the clusters to which K8s rolls out the resources. To distribute the pods on both sides of the cluster, you need to feed them in differently.

Listing 2: Federated Namespace

---

apiVersion: types.kubefed.io/v1beta1

kind: FederatedNamespace

metadata:

name: fedns

namespace: fedtestns

spec:

placement:

clusters:

- name: earth

- name: vulcan

A simple web server is used as a test case. Normal unfederated deployment results in the pods running in the local cluster only. The command for federating the namespace along with its contents distributes all the existing resources but does not ensure that newly created resources are also evenly distributed in the same way. You now have the option of creating a deployment directly as a FederatedDeployment instead. The YAML file for this is shown in Listing 3. It looks very similar to the one for a simple deployment, but the placement parameter ensures that the specified clusters also inherit the deployment.

Listing 3: Federated Deployment

apiVersion: types.kubefed.io/v1beta1

kind: FederatedDeployment

metadata:

name: fedhttp

namespace: fedtestns

spec:

template:

metadata:

name: http

spec:

replicas: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app: httpbin

version: v1

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: httpbin

version: v1

spec:

containers:

- image: docker.io/kennethreitz/httpbin

imagePullPolicy: IfNotPresent

name: httpbin

ports:

- containerPort: 80

placement:

clusters:

- name: earth

- name: vulcan

After a short wait, you will now have a pod and a deployment with the web service on both clusters. The pods on both clusters can also be accessed on port 80. In the case of AWS, however, you also need to enable this port in the correct security group of the AWS configuration.

For the pods in the clusters to work together, it is crucial to set up routing between the two clusters so that they can reach each other. You also need to configure firewall rules and security groups appropriately. It is advisable here to rely on an automation tool such as Ansible if the cluster at the cloud provider's end will be on-demand only.

Like the deployment, you also need to roll out the service as a FederatedService, if you use it. Listing 4 shows the service for deployment from Listing 3, with service name resolution running locally; that is, fed-service resolves to the cluster IP in the local cluster. This feature is something to keep in mind when designing the service.

Listing 4: Federated Service

apiVersion: types.kubefed.io/v1beta1

kind: FederatedService

metadata:

name: fed-service

namespace: fedtestns

spec:

template:

spec:

selector:

app: httpbin

type: NodePort

ports:

- name: http

port: 80

placement:

clusters:

- name: earth

- name: vulcan

Components such as persistent volumes are also created locally on the clusters and must be populated there. Where pods access remote resources, you need to make sure they are accessible on both clusters. It is important to consider both IP accessibility and name resolution.

If you remove the federated resources, you remove the resources at the same time. To remove only one cluster from the deployment, remove the cluster under placement. You can remove the second cluster from the configuration with the command:

# kubefedctl unjoin vulcan --host-cluster-context earth --v=2

In the test, however, I did have to manually clean up the resources rolled out in the second cluster retroactively. You can save yourself this step by completely deleting the cluster from the commercial public cloud provider.

Conclusions

Kubernetes Cluster Federation makes it easy to link up one or multiple clusters as resource extensions. This solution doesn't mean you don't have to pay attention to what will be running where, and it is important to set up the extension such that the service's consumers can use it.

In the case of a special promo in a web store, for example, the customers' requests need to reach the containers in the new cluster in the same way they did at the previously existing clusters; otherwise, federation will not offer you any performance benefits. If you expect such situations to occur frequently, it is advisable to run your own cluster as a federation with a single member. Then, you only need to complete the steps required for the extension.

Ready to find a job? Check out the latest job listings at Open Source JobHub.

This article originally appeared in ADMIN magazine and is reprinted here with permission.

Want to read more? Check out the latest edition of ADMIN Network & Security.

Comments